Our content is free to use with appropriate credit. See the terms.

The insurrection at the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021, will forever be remembered as one of the darkest days in American history.

Thousands converged to support then-President Donald Trump and his false claims that he was the victor over Joe Biden in the 2020 election. “If you don’t fight like hell,” Trump told the masses, “you’re not going to have a country anymore.”

Soon after, demonstrators wearing “Make America Great Again” baseball caps and, in some cases, full riot gear assaulted police, smashed windows and stormed the Capitol building, intent on blocking certification of the results.

Nearly four years later, more than 1,400 people have been charged in connection with the insurrection. Some have no regrets. Others brim with remorse. “You don’t want to tell people you’re a Jan. 6er,” one says. “It’s not something to be proud of.”

Meanwhile, those who stood against the mob still carry physical and emotional scars.

Four people who were there gave News21 access to their daily lives to share the enduring impact of that day.

These are their stories.

PAMELA HEMPHILL

Pamela Hemphill drives through Boise, Idaho, on June 17, 2024. Hemphill served two months in prison for her actions during the Capitol insurrection. (Photo by Donovan Johnson/News21)

With her phone attached to a selfie stick, Pamela Hemphill filmed as the mob pushed past law enforcement and made its way into the Capitol building on Jan. 6.

“I was just as much a MAGA as all the MAGAs in believing that the election was stolen,” the now-71-year-old says.

Hemphill reflects on her role at the Capitol riot from her apartment in Boise. Hemphill says she was “just as much a MAGA as all the MAGAs” back then. Today, she no longer supports Donald Trump. (Photo by Donovan Johnson/News21)

Today, Hemphill is committed to electing Vice President Kamala Harris – not Trump – come November, and to making amends for her participation in what she calls the most horrible day in America.

“It’s like breaking your leg, but you always have a limp,” she says. “I’m always going to have a limp.”

“It’s like breaking your leg, but you always have a limp. I’m always going to have a limp,” Hemphill says of her participation in the Jan. 6 riot. (Photo by Donovan Johnson/News21)

Hemphill was 41 years sober when she stepped onto the Capitol grounds, a decision that would alter her life. A grandmother, cancer survivor and recovering alcoholic, Hemphill served two months in prison and another 36 months on probation.

Now living in Boise, Idaho, she says she wants to leverage her past as a right-wing activist, Trump supporter and addict to help others who, like her, might base bad decisions on disinformation.

Hemphill, at a recent pro-Palestinian demonstration in Boise, says she wants to draw on past mistakes to make amends for her actions and to help others. (Photos by Donovan Johnson/News21)

“They say in (Alcoholics Anonymous) our past is our greatest asset, because with it we can help others if we recognize that we were wrong and make amends,” Hemphill says. “So that’s what this is all about: making amends for that horrible day that I can never live down.”

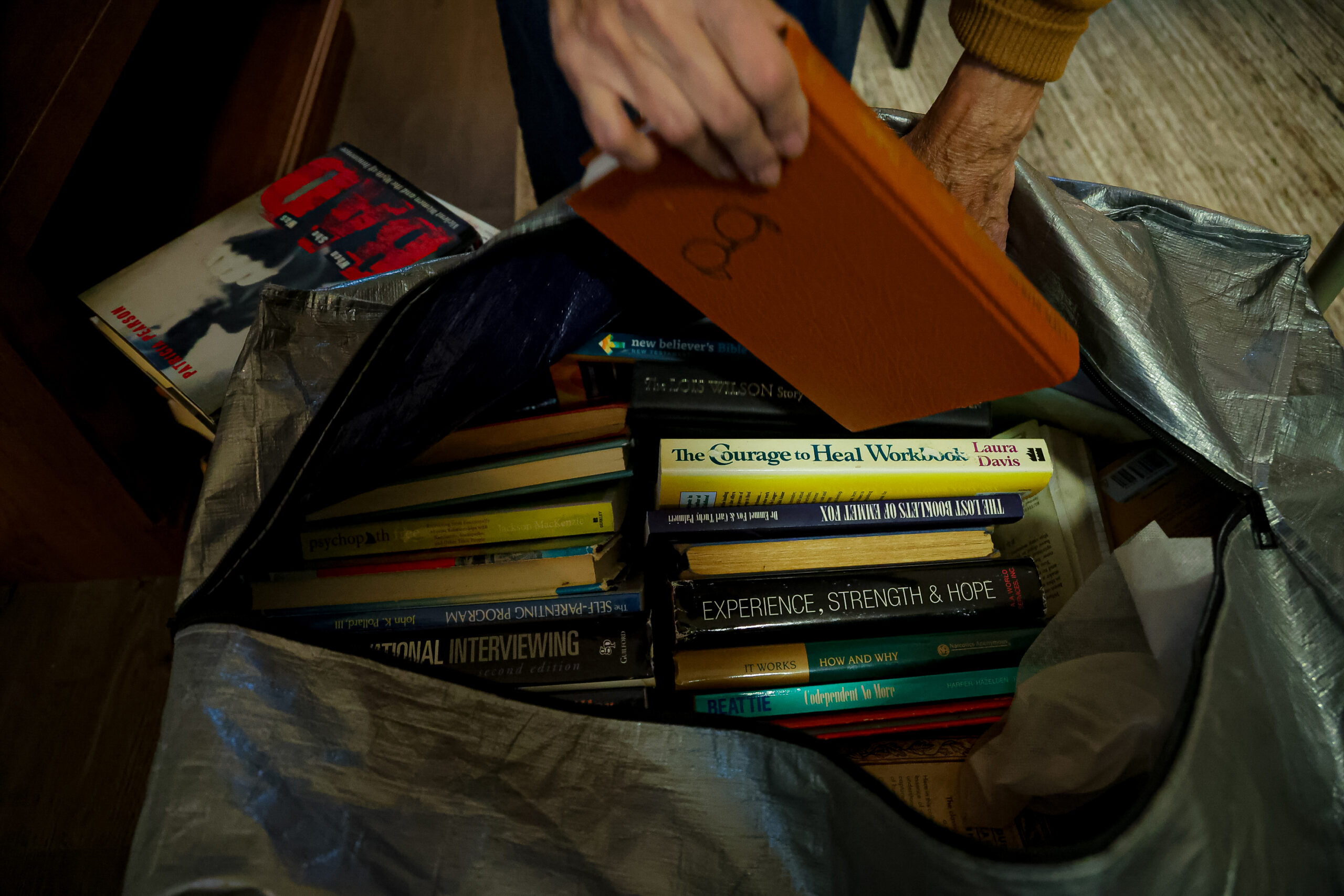

Hemphill recently returned to Boise – to the same apartment building, though a different unit, that she lived in before going to prison. Friends David Vincent, left, and Loyd Gibbons, right, help her unpack her belongings. (Photos by Donovan Johnson/News21)

Hemphill says she fell into a deep depression after the riot, prompting her to seek help from AA, a safe haven for her since she was 27.

“It doesn’t matter how long you’re sober – you can go into denial in any area of your life,” she says. “You could be in a bad relationship, a bad job, doing things like I did on Jan. 6. It’s not like the program restores you to sanity immediately. Character defects are still glaring. I have a lot of them.”

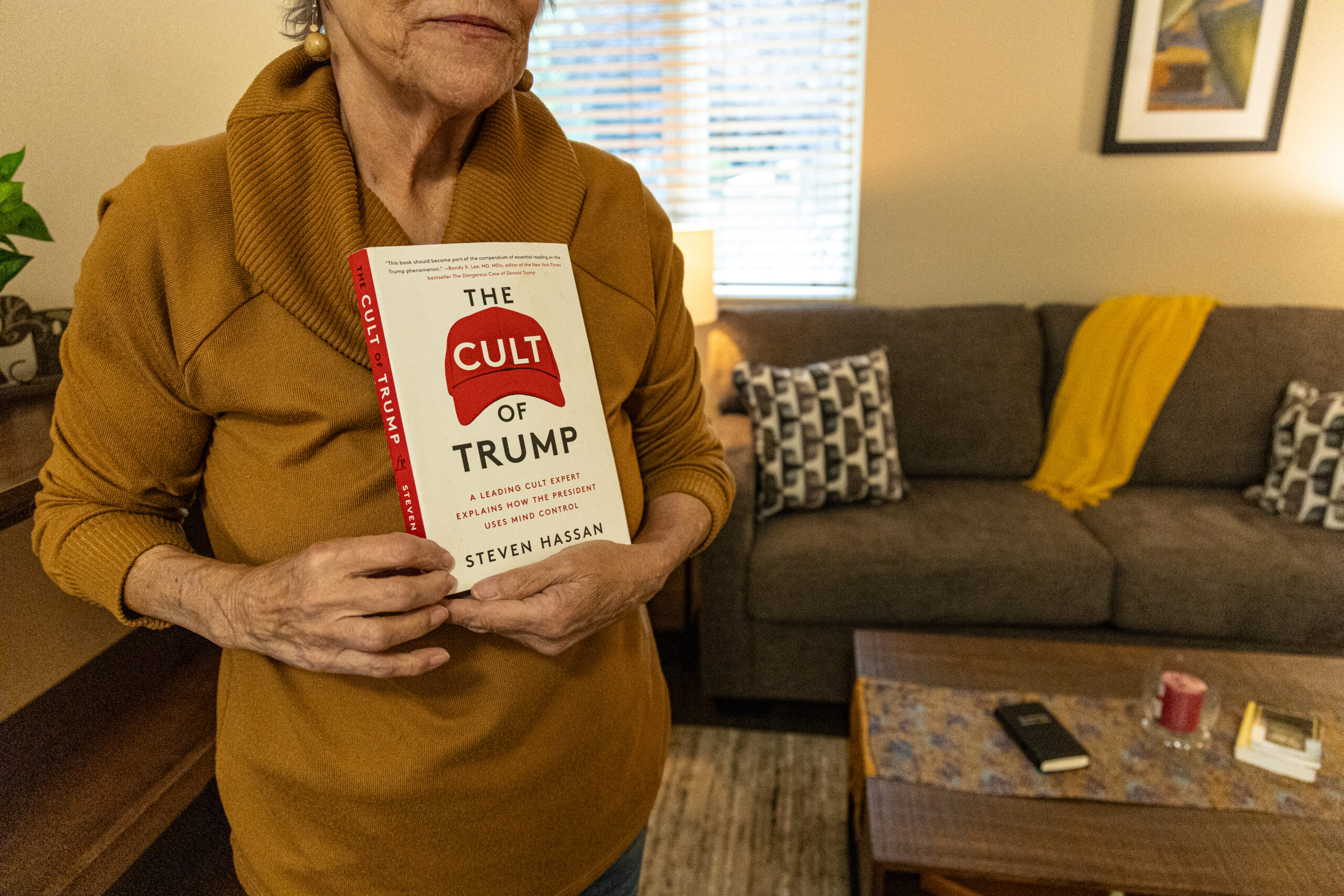

Hemphill shares her Jan. 6 experience on social media and in interviews, warning others about what she calls the “cult” of Trumpism. “I’m frightened for democracy right now,” she says. (Photo by Donovan Johnson/News21)

Since her release from federal prison, Hemphill has shared her experience on social media and in interviews, speaking out against Trump, whom she calls a “narcissist.”

“It’s part of my ways of making amends for that horrible day, the most horrible day of our nation,” she says. “You never can really make amends, per se, to make it right. But I’ll try to do the best I can to let the nation know I am so sorry.”

Hemphill holds her dog, Pork Chop, inside her apartment. (Photo by Donovan Johnson/News21)

Hemphill says she fell into a deep depression after Jan. 6, prompting her to seek help from Alcoholics Anonymous, a safe haven for her for decades. (Photo by Donovan Johnson/News21)

When asked if she regrets her actions on Jan. 6, Hemphill says: “I can’t stay stuck in the past, in the guilt and the shame, but that’s where I was for a long time – and I’m still a little bit.

“You don’t want to tell people you’re a Jan. 6er. It’s not something to be proud of.”

NATHAN DeGRAVE

Former Jan. 6er Nathan DeGrave leans against the First Baptist Church of Henderson, Nev., after attending a screening of a documentary about the insurrection. (Photo by Hudson French/News21)

Nathan DeGrave, 35, spent a year and a half in jail and six months in federal prison for his role in the insurrection, then was transferred to a halfway house in Las Vegas to serve the rest of his 37-month sentence.

Leading up to Jan. 6, DeGrave says he didn’t believe the 2020 election was fair. He was working 16-hour days at his marketing company, so when a friend told him he was going to the Capitol to rally on Trump’s behalf, DeGrave says he viewed it as a break and went along.

This display greeted those attending a recent screening of “Let My People Go,” a documentary that portrays the imprisonment of Jan. 6 felons as a “form of slavery.” (Photo by Hudson French/News21)

A trailer plastered with signs sits outside a Nevada church during a screening of a documentary about Jan. 6ers. DeGrave was invited to speak at the premiere. (Photos by Hudson French/News21)

According to court documents, the car DeGrave and his companions drove to the Capitol contained paramilitary gear, a Glock pistol, an M&P Bodyguard pocket pistol, two magazines of ammunition, knives, a stun gun, an expandable baton, two-way radios and bear mace.

DeGrave was among the crowd that pushed against officers to force open the Capitol rotunda doors, “allowing the mob outside to begin streaming in,” according to court records. Once inside, he joined in a “shoving match” with police who tried to block rioters from entering the Senate gallery.

DeGrave holds up some “Trump money.” He remains a fervent Trump supporter, and says Jan. 6 “was an opportunity for us to finally speak out after being silenced for so long.” (Photo by Hudson French/News21)

In 2022, DeGrave pleaded guilty to two counts: conspiracy to obstruct a proceeding and assaulting, resisting or impeding officers. He says Jan. 6 “was an opportunity for us to finally speak out after being silenced for so long.”

Although he wasn’t close with his family before, DeGrave says he hasn’t spoken to his mother since the insurrection, and he’s lost touch with other relatives and some friends. He nevertheless says his life now is even better than before.

DeGrave says he does not feel “any shame” for his participation in the riot. Like some other Jan. 6ers, he considers himself a “political prisoner” – and he remains a fervent backer of Trump.

DeGrave spent a year and a half in jail and six months in federal prison for his role in the insurrection, then was transferred to a halfway house in Las Vegas. (Photo by Hudson French/News21)

In June, DeGrave attended a Trump rally in Las Vegas. He wore a shirt emblazoned with a photo of himself in full riot gear on Jan. 6 and approached reporters to offer interviews.

“I stormed the Capitol,” he told News21.

Later that month, DeGrave was invited to speak at a local church for the premiere of “Let My People Go,” a documentary that portrays the imprisonment of Jan. 6 felons as a “form of slavery.” At the screening, viewers asked to pose for photos with him, thanking him for his actions and calling him a “hero.”

DeGrave speaks to the audience at a screening of “Let My People Go.” DeGrave doesn’t believe the 2020 election was fair. On Jan. 6, he was among the crowd that pushed against officers to force open the Capitol rotunda doors. (Photo by Hudson French/News21)

At the Jan. 6 documentary screening, viewers thanked DeGrave for his actions and called him a “hero.” (Photo by Hudson French/News21)

DeGrave poses with, from left to right, Kristen Ditto, Mike Hutchings and R.J. Hutchings after a screening of “Let My People Go.” (Photo by Hudson French/News21)

DeGrave said he regrets having made anyone feel unsafe, but he stands by his actions.

“I think Jan. 6 was a warning shot – it’s nothing compared to what could happen,” he says. “The problems that are exacerbating and creating these situations are not being addressed. We’re shoving it down and we’re shoving it down until, eventually, the public and the American people reach a breaking point.”

He adds: “I don’t feel any shame about what I did.”

DeGrave and Nathan Van Tuyl, right, record a podcast about DeGrave’s experience at the insurrection. DeGrave says he stands by his actions and he’ll continue to speak out. (Photo by Hudson French/News21)

DANIEL HODGES AND AQUILINO GONELL

Aquilino Gonell, far left, and Daniel Hodges, third from the left, testify with two other police officers before the House committee that investigated the Capitol insurrection. (Photo by Andrew Harnik-Pool/Getty Images)

Daniel Hodges and Aquilino Gonell are two of the 140 police officers who were assaulted during the attack on the Capitol. They continue to share their experiences about that day and advocate for the future of democracy in the United States.

Hodges, 36, has served with the Metropolitan Police Department in Washington, D.C., for more than nine years. On Jan. 6, 2021, he and his platoon responded to the west terrace of the Capitol.

Hodges has been with the Metropolitan Police Department for more than nine years. He was among 140 police officers who were assaulted during the attack on the Capitol. (Photo by Donovan Johnson/News21)

“I was knocked to the ground by someone trying to steal my baton, who kicked me in the chest, and my medical mask got pulled up over my eyes,” Hodges recalls. “I was blind and on all fours, surrounded by the mob. I thought I was gonna get torn apart at that point.”

A Connecticut man who used a police riot shield to pin Hodges against a door was sentenced to seven and a half years in prison for nine offenses. In court records, the attacker’s lawyer said he was “motivated by a misunderstanding as to the facts surrounding the 2020 election” and had “listened to sources of information that were clearly false.”

Video turned over to the U.S. House committee that investigated the insurrection shows Hodges being jammed against a door.

A Texas man responsible for pulling Hodges’ mask off was sentenced to seven years in prison and two years of supervised release for multiple felony charges. Court documents say that during the attack, he jeered at Hodges: “How do you like me now, f****r?!” He then grabbed Hodges’ riot baton and hit him over the head.

“Throughout this assault, Officer Hodges screamed and pleaded for help,” court records say.

In the aftermath of the attack, Hodges testified before the congressional committee that investigated the insurrection. He’s also made several public appearances.

“I feel a moral obligation to speak the truth about what happened that day and try to steer the world toward a more just and equitable exercise of our government,” he says.

Left: Hodges enjoys some downtime at his home in Maryland. Right: Hodges gets ready for his night shift. He continues to speak out about what happened to him on Jan. 6. He feels a “moral obligation,” he says. (Photos by Donovan Johnson/News21)

While Hodges fulfills his duties as a police officer, he’s also studying for a bachelor’s degree in interdisciplinary studies. He wants to learn more about the country and its history.

Hodges says it’s up to all U.S. citizens to be curious about the nation they live in and to be active participants in democracy.

In addition to his police work, Hodges is studying for a bachelor’s degree in interdisciplinary studies. (Photo by Donovan Johnson/News21)

“Democracy is only as strong as the people who believe in it and the people who participate in it,” he says. “So it is up to us.”

Hodges was awarded the Presidential Citizens Medal by President Joe Biden on the second anniversary of the attack. The medal is given to those who perform exemplary deeds for their country or fellow citizens.

Hodges was awarded the Presidential Citizens Medal by President Joe Biden on the second anniversary of the insurrection. attack. He displays it at his home. (Photo by Donovan Johnson/News21)

To those who have called the police officers who defended the Capitol “traitors” or spewed conspiracy theories that the attack was an “inside job” orchestrated by undercover agents, Hodges responds: “It’s not us who were the traitors.”

“We were defending the United States Capitol. We were defending the peaceful transfer of power,” he adds. “The mob were the ones who had laid siege to the Capitol of the United States. There’s really no reasonable way to understand its defenders as traitors.”

Gonell holds a frame displaying glass shards and rubber bullets collected from the Jan. 6 riot. He keeps them as a reminder of what he went through. (Photo by Donovan Johnson/News21)

Gonell, 45, came to the United States from the Dominican Republic when he was 12 years old – searching, like so many others, for the American dream. He served in Iraq with the U.S. Army after the Sept. 11, 2001, terror attacks.

“I wanted to serve this country,” he says, “and give back some of the things that were given to me.”

Before joining the U.S. Capitol Police, Gonell served in Iraq with the U.S. Army. His Army uniform hangs from a gazebo in Occoquan, Va., on July 2, 2024. (Photo by Donovan Johnson/News21)

In 2006, he continued that service, joining the U.S. Capitol Police as an officer. And he says what he experienced on Jan. 6 was “a lot worse” than his deployment in Iraq.

On the day of the insurrection, Gonell joined other officers who tried to stop rioters from entering the Capitol through the west terrace tunnel. That tunnel would become the site of some of the most violent attacks against law enforcement.

While trapped in the tunnel, Gonell says, he “nearly died being crushed.” For more than three hours, he was pushed, punched and kicked by more than 40 people. He later required two surgeries to repair his left shoulder and right foot after being dragged by rioters.

Those are the most severe injuries, he says. But also: “Contusions, lacerations, both my hands were bleeding at some point.”

Despite the pain, Gonell continued doing his job – defending the Capitol and those inside. “I knew what was at stake,” he says. “Some people might see a clip of me walking around fine, but I wasn’t fine.”

In December 2022, Gonell left the police force to focus on healing his physical and emotional wounds.

“Having to return to the scene of the crime almost every day has become taxing, unbearable and not conducive to healing,” he wrote in his resignation letter. “I will always support and defend the United States and my fellow police officers as they stand between order and chaos.”

As an immigrant, Gonell finds it hypocritical when Trump and other Republicans rail about an “invasion” at the southern border. “The only invasion that I’m worried about is another Jan. 6,” he says. “This was done by mainly native U.S. citizens.”

In December 2022, Gonell left the police force to focus on healing his physical and emotional wounds. He regularly does interviews because he says he wants “accountability for what happened, justice for what happened.” (Photo by Donovan Johnson/News21)

Gonell has testified before Congress and appeared on national television to dispute conspiracy theories about police officers who were on duty Jan. 6. More than anything, he says, he wants those who participated in the attack to take full responsibility.

Last year, a Michigan man connected with a militia group was sentenced to four years in prison for striking Gonell with a stolen police baton. A second man, from Idaho, received four years for also assaulting Gonell.

In a 2022 victim impact statement, Gonell said he’d installed cameras at his home to ease his family’s concerns about retaliation and attended biweekly counseling sessions to help him cope with lingering psychological trauma.

“For many Americans,” he wrote, “ the tragic and horrific events of January 6th concluded after a few hours or that day after. However, for me, it has not ended. January 6th continues every day.”

Gonell walks through a forest in Occoquan, Va., with his dog, Milo. (Photo by Donovan Johnson/News21)

Today, Gonell spends most of his downtime in nature, which helps him clear his mind. And he continues to speak out about what happened that January day in Washington.

“At the end of the day, that’s what I want – accountability for what happened, justice for what happened,” he says. “We were outnumbered because of the sheer fact that the former president sent people to the Capitol and didn’t do anything to stop it.

“Everything that I do is for my ancestors, our forefathers and people who fought wars and made so many sacrifices for our country. Will they be OK with what the country is – or is becoming?”

News21 reporter Josie Malave contributed to this story.

People walk in front of the U.S. Capitol on July 2, 2024. (Photo by Donovan Johnson/News21)