(Video by Josie Malave/News21)

Our content is free to use with appropriate credit. See the terms.

BOISE, Idaho – Pamela Hemphill was on the front lines of the mob that stormed the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021. Days before, she had posted to social media: “It’s not going to be a FUN Trump Rally … its a WAR! The fight for America is REAL.”

Three years later, her perspective and alliances have changed.

“I was just as much a MAGA as all the MAGAs in believing that the election was stolen and thinking that I was being a part of something to help save our nation,” the 71-year-old says.

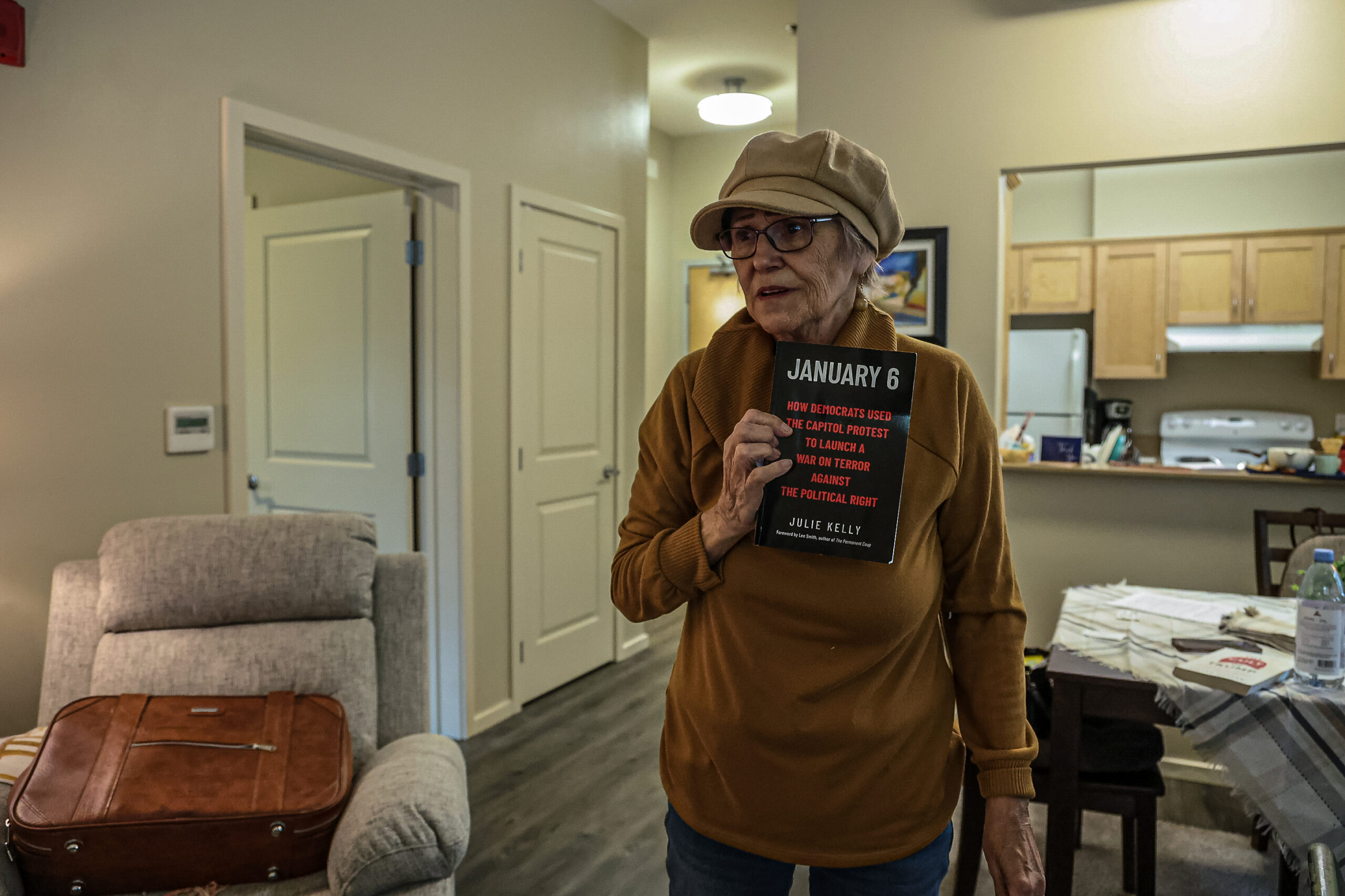

She recently returned to Boise – to the same apartment building, though a different unit, that she lived in before she surrendered to federal prison to serve two months for her role in the riot.

Hemphill is completing the remainder of her 36-month probation, and she’s on a personal mission to make amends for her actions and warn others about what she calls the “cult” of Trumpism.

“I’m frightened for democracy right now,” she says.

Pamela Hemphill, inside her apartment in Boise, Idaho, on June 17, 2024, holds one of the many books she read after the insurrection at the U.S. Capitol. (Photo by Donovan Johnson/News21)

It’s been a common refrain this election year: Democracy itself is at stake. Political pundits, worried voters and President Joe Biden have all made the claim, insisting that should Donald Trump take office again, he will destroy the very foundations upon which the country was built.

Those assertions briefly abated after the July assassination attempt on Trump – an act that rattled the nation and brought calls to tone down the heated “threat to democracy” rhetoric.

But some questions nevertheless beg exploration: What is the lasting impact of Trump, and Trumpism, on American democracy? And what might the future hold if he wins in November?

Left: An attendee wears a Trump 2024 flag outside Dream City Church in Phoenix on June 6, 2024. The rally was former President Donald Trump’s first public appearance following his felony conviction in New York. Right: Antoinette Degnaro wears an American flag-themed outfit at a rally for Trump at Dream City Church in Phoenix. (Photos by Jordan Moore/News21)

‘The Big Lie’

Richard Abel, a professor at UCLA’s School of Law, says three mechanisms hold a president to account: the electoral process, impeachment and the judicial system.

Trump, he and others contend, has worked to undermine all three.

Abel has long studied Trump’s rise and authored the 2024 book “How Autocrats Seek Power: Resistance to Trump and Trumpism.”

“Trump has explicitly repudiated any sense of obligation or loyalty to the most basic institutions of American society,” he says. “My fear is that he will wreak so much havoc on fundamental American institutions in a second term that the results will be irrevocable.”

Trump’s refusal to accept the outcome of the 2020 election, culminating in the insurrection at the Capitol, is to many legal and constitutional experts the starkest example of how democracy has diminished in the era of Trump.

Shortly after that race was called for Biden, Trump began a monthslong campaign of lies about widespread fraud, publicly and privately pressuring federal and state officials to investigate and reverse the outcome.

His efforts resonated with thousands who falsely believed they were saving the country from a stolen election when they stormed the Capitol as Congress certified the results.

Hemphill filmed the events of that day, documenting the massive crowd as it moved from where Trump gave a rousing speech outside the White House to the Capitol grounds, where rioters smashed windows and assaulted police. In one video, Hemphill seeks safety behind law enforcement officers as they try to hold the rioters back.

She would go on to be one of thousands who entered the Capitol building that day, against orders from the police who protected her.

Former President Donald Trump raises his fist at the Republican National Convention in Milwaukee on July 16, 2024. (Photo by Hudson French/News21)

“It was kind of exciting, in a way, that we’re all there supporting our country. We are patriots. That’s the attitude at the time. Of course, I know we’re not,” says Hemphill, who now calls Trump a “dangerous narcissist” who “wants to be a dictator.”

Capitol Police Sgt. Aquilino Gonell was dispatched to defend the Capitol. Gonell says he was trampled, stomped and assaulted by rioters as he risked his life to protect those inside and his fellow officers.

“Both my hands were bleeding at some point, swollen,” he says. “I continued to do my job that day because I knew what was at stake.”

Gonell is outspoken about the physical and emotional trauma he suffered – wounds that forced him into an early retirement. Since the attack, he has testified in court and before Congress, made media appearances and campaigned against Trump. His goal: accountability and justice.

“Somebody told them – invoked them – to come to the Capitol on that day,” Gonell says. “And who was that person? It was not Nancy Pelosi. It was not Capitol Police. … It was Donald Trump.”

Former President Donald Trump gestures to the crowd as he exits the second night of the Republican National Convention. (Photo by Hudson French/News21)

Some Trump supporters view his involvement differently, and Trump himself insists he was not responsible for the violence.

“He was just a voice for us,” says Nathan DeGrave, one of more than 1,400 people so far charged in connection with the riot. “It’s not necessarily that he made these statements that then caused us to act. It was more so him repeating what we already knew to be true, and the American people acted on their own accord.”

DeGrave donned a full suit of riot gear and carried a can of bear mace as he pushed past officers to enter the Capitol. He was sentenced to 37 months in federal custody and served much of that in a halfway house in Las Vegas.

That morning, Trump told supporters “to peacefully and patriotically make your voices heard.” But he also said: “If you don’t fight like hell, you’re not going to have a country anymore.”

Unlike Hemphill, DeGrave continues to support Trump and wears his identity as a Jan. 6 participant like a badge of honor. At a June Trump rally in Las Vegas, DeGrave sported a shirt printed with a photo of himself outside the Capitol that day.

“Our intentions were not to overthrow the government or try to change their mind,” he says. “It was just more so about making that statement that we felt like we were unheard and our voices were repressed.”

The peaceful transfer of power is a “bedrock principle of democracy,” says Stanley Feldman, a political psychologist at New York’s Stony Brook University. Trump’s efforts to convince voters the election was stolen, just because the results were unfavorable, damages that principle, he says.

“The fact that there so far has been zero evidence that there was anything wrong with the 2020 election doesn’t really matter to the extent to which he’s convinced a sizable segment of voters that the election was stolen, that there are forces conspiring to prevent him from winning a fair election,” Feldman says.

The congressional committee that investigated Jan. 6 found Trump “purposely disseminated false allegations of fraud” and that those false claims “provoked his supporters to violence.”

Last year, a federal grand jury indicted Trump on four felony counts related to his actions, but that case hangs in limbo after the U.S. Supreme Court ruled this summer that presidents may be immune from criminal prosecution for “official acts.”

Protesters demonstrate outside of the U.S. Supreme Court in Washington, D.C., before the presidential immunity decision on July 1, 2024. The high court ruled that presidents may be immune from criminal prosecution for “official acts.” (Photo by Donovan Johnson/News21)

A lower court must now decide whether Trump’s conduct on Jan. 6 is protected or not. Critics, meanwhile, say the ruling further imperils democracy. In her dissent, Justice Sonia Sotomayor said the decision “reshapes the institution of the presidency. It makes a mockery of the principle, foundational to our Constitution and system of government, that no man is above the law.”

In a May interview with the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, Trump said he would accept the results of this year’s election “if everything’s honest.”

“If it’s not,” he said, “you have to fight for the right of the country.”

High crimes and misdemeanors

After the Capitol riot, the House impeached Trump for incitement of insurrection. The Senate acquitted him, but it wasn’t the first time he had faced impeachment for his conduct as the nation’s leader.

In 2019, Trump also was impeached, and later acquitted, for pressuring then-newly elected Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky to announce investigations involving the Biden family and conditioning nearly $400 million in aid on whether Zelensky acted.

Two other presidents have been impeached – Bill Clinton in 1998 and Andrew Johnson in 1868. But Trump is the only president to be impeached twice while in office.

Seven Republican senators joined Democrats to vote to convict Trump in the insurrection case. Despite that, political historian Allan Lichtman says, “This is now a Trump Republican Party. There’s virtually no Republican leader willing to stand up to him.”

Trump’s legal woes aren’t restricted to the impeachment cases.

After he left office in 2021, he was charged with 91 counts across four cases related to the insurrection, efforts to overturn Georgia’s 2020 results, mishandling of classified documents and falsifying records to cover up paying an adult film actress to stay quiet about their alleged affair.

In that last case, a jury convicted Trump on 34 counts. Moments after becoming the first former president to be marked as a felon, Trump called the case a “rigged, disgraceful trial” with a “corrupt” judge and accused the Biden administration of orchestrating the case.

His sentencing was delayed so the judge can determine whether evidence used in the case is protected under the Supreme Court’s immunity decision. The other cases also remain up in the air because of ongoing court challenges.

Trump’s public comments about these cases are especially concerning to Lichtman, who has written several books about the nation’s 45th president, including “Thirteen Cracks: Repairing American Democracy After Trump.”

“In order to sustain the sovereignty of the people, you have to have strong institutions – led, of course, by a strong, independent justice system,” Lichtman says. “Trump has responded to his legal troubles by attempting to destroy our system of justice, which is a pillar of our democracy.”

Trump’s verbal attacks on jurors and others involved in the New York case led the judge to issue a gag order restricting him from harassing or disruptive conduct. He was fined $9,000 for violating that order.

“In every instance, he attacks the judges, the prosecutors, lawyers, the witnesses, the jurors – everybody in sight,” says Abel, the UCLA professor. “And it does terrible things to people’s belief in the legal system.”

Trump and other Republicans maintain the criminal cases are politically motivated. In a June New York Times/Siena poll, 49% of registered voters agreed with that contention. Among Republicans, that number soared to 90%, and 68% of respondents said Trump’s conviction wouldn’t affect whether or not they would vote for him in November.

Left: Former President Donald Trump’s mugshot on a T-shirt seen through an American flag scarf outside the candidate’s rally in Las Vegas on June 9, 2024. Right: A woman fans herself while waiting in line at Trump’s rally in Las Vegas. (Photos by Jordan Moore/News21)

A week after his conviction, Trump hosted campaign events in Phoenix and Las Vegas. Despite extreme heat, thousands turned out – some wearing T-shirts with Trump’s mugshot and the declaration “I’m Voting for the Felon.”

Rose Valencia, a Las Vegas resident who attended the rally there, said she has supported Trump since his first campaign and thinks the legal cases against him are a “clown show” and “circus.”

“They’re just trying to get him off the campaign trail,” Valencia said. “They’re trying to keep him off the stage, and the people are tired of it. I’m tired of it.”

Politics of division

A hallmark of Trump’s brand of politics has been attacking “the other,” experts say. And although polarization in politics didn’t originate with him, they say it has deepened as culture wars over abortion, immigration, racial equality and LGBTQ rights have grown more fierce.

“We are rapidly heading to becoming a majority-minority nation,” Lichtman says. “This has spurred deep-seated fears among some … that America is changing in a way that imperils their lives and their cultural and religious beliefs.”

Adds Charles Hunt, a political science professor at Boise State University: “(Trump’s) whole slogan is ‘Make America Great Again,’ meaning that we were better off before all of this uncertainty, we were better off before all of this change. Underneath a lot of that stuff are some pretty incendiary racial and ethnic undertones.”

Licthman and Hunt argue that stoking those anxieties further threatens the ties that bind the nation.

Trump announced his first presidential campaign with a speech calling Mexican immigrants criminals and rapists. That rhetoric has not softened. In his acceptance speech at this year’s Republican National Convention, he called the influx of immigrants “the greatest invasion in history,” even though crossings at the southern border have decreased in recent months.

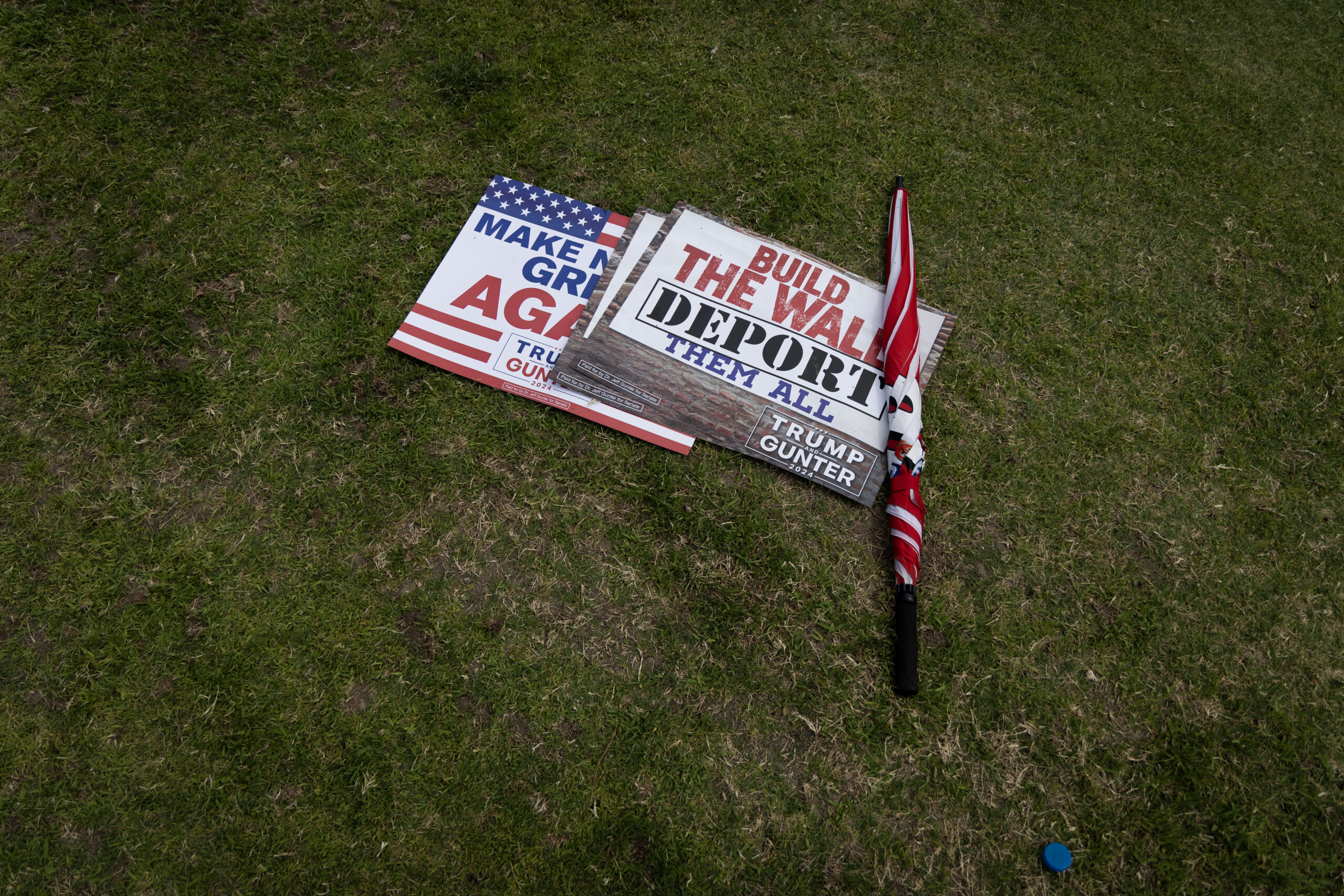

Left: Attendees, holding signs that read “Mass Deportation Now,” look toward the stage during the Republican National Convention in Milwaukee on July 17, 2024. (Photo by Hudson French/News21) Right: Campaign signs lay on the grass outside a Trump rally in Las Vegas in June. (Photo by Jordan Moore/News21)

Some say such language plays off of, and further feeds, fear of change during a time of shifting demographics. It can also fuel extremist groups such as the Proud Boys and Oath Keepers, whose members helped lead the charge during the insurrection.

“If Trump is elected, I think it emboldens a lot of these groups in ways that are very concerning,” Kathleen Belew, a historian at Northwestern University who studies extremist groups, said in a lecture earlier this year at Arizona State University. She noted Trump has pledged to pardon Jan. 6 participants, whom he calls “hostages” and “patriots.”

Others say Trump has also emboldened those in the Christian nationalist movement, who advocate for America to return to what they believe are its Judeo-Christian origins and, ultimately, for the elimination of the separation between church and state.

Left: A woman wears a pendant of Jesus Christ next to one showing her support for Donald Trump. (Photo by Jordan Moore/News21) Right: A Texas delegate shows off his T-shirt on the third night of the 2024 Republican National Convention. (Photo by Hudson French/News21)

“Our future, our identity, and our very way of life are under threat like never before,” reads the preamble to the platform adopted in July by the Republican National Committee.

It goes on to list 20 promises for a second Trump administration, including closing the border, carrying out a mass deportation operation, cutting federal funding for schools that teach “critical race theory” and “radical gender ideology,” and securing elections.

It also recommends a new federal task force, on fighting “anti-Christian” bias, that would investigate “discrimination, harassment and persecution against Christians.”

“Trump and his people, and Christian nationalist leaders and their people, they both swim in the tactic of apocalyptic crisis,” says Brad Onishi, a religious scholar who studies Christian nationalism.

That’s led many Americans to believe Trump “is the singular figure who can save them,” Onishi says. “That is a recipe for authoritarianism. It’s a recipe, oftentimes, for fascism. And it’s really dangerous.”

Others share the concern that the U.S. could be on the path of morphing from democratic to authoritarian, pointing to Trump’s embrace of Viktor Orbán, the prime minister of Hungary whose anti-democratic moves in that country worry leaders in the European Union and NATO.

Two days before the Republican National Convention kicked off in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, the Rev. Marilyn Miller sat within the walls of the city’s Helene Zelazo Center for the Performing Arts, reflecting on Trump and the state of the nation.

“A lot of things that come out of his mouth are very divisive – they don’t make people like me feel like I belong in America,” said Miller, who is Black.

Miller, the former president of Milwaukee Inner-City Congregations Allied for Hope, was preparing for a rally the following day to counter Christian nationalism and urge people of all faiths to protect democracy.

“We’re a democracy now,” she said, “but we could become something else if we’re not careful.”

Hero or villain?

Left: A crowd protests former President Donald Trump during the first day of the 2024 Republican National Convention in Milwaukee. Right: An attendee looks toward the stage during the opening day of the Republican National Convention. (Photos by Hudson French/News21)

On the first day of the convention – two days after the assassination attempt – GOP delegates and Trump supporters from across the nation gathered to see him formally nominated, again, as the Republican candidate for president.

The intensity of their adoration was on full display.

When asked what makes him unique, one man said, “I’ll make it short: I think he’s a strong man with good ideas.” Another called him “the alpha” among other would-be nominees – “a pretty bold guy.”

Joshua Dismukes, a paramedic, traveled from Golden Meadow, Louisiana, to be at the event.

Dismukes said he wholeheartedly believes Trump will “fix everything.”

“I think we will have a booming economy. I think our justice system will be fixed. I think our corrupt judges will be fixed,” he said. More than anything, Dismukes said, he believes that Trump will get America “back to being America, the way it was meant to be.”

In his acceptance speech, Trump initially struck a chord of unity.

“Together, we will launch a new era of safety, prosperity and freedom for citizens of every race, religion, color and creed. The discord and division in our society must be healed,” he said, adding: “We rise together. Or we fall apart.”

And to those who have labeled him “an enemy of democracy,” he said: “In fact, I am the one saving democracy for the people of our country.”

A June poll shows that 44% of swing-state voters agree, trusting Trump to handle threats to democracy over Biden.

He then spent more than an hour returning to some of the rhetoric of old, talking about the “invasion” at the border, accusing Democrats of using “COVID to cheat” in the 2020 election and painting a doomsday picture of the country today.

Earlier that week, Milwaukee residents Michelle Adams and Romie Bolden sat outside a building near the Republican convention, watching attendees walk up and down the street as police officers surveyed the area. Bolden, a retired machinist, said the Republican Party should be “banned” for standing behind a “crook” like Trump.

Unlike Dismukes, Bolden fears what might happen if Trump is reelected. As he and Adams watched officers patrol the streets, Bolden pointed at what he thought to be a sign of dangerous times to come.

“You see those cops there riding on the bikes, and the fences there? You can expect some more of that, because he has free rein to do whatever he wants to do,” Bolden said. “This will become a police state.”

Members of the Milwaukee Police Department stand with their bikes in downtown Milwaukee on Monday, July 15, 2024. (Photo by Hudson French/News21)

Sitting across the street from Adams and Bolden was Jesse Boggs, a Trump supporter from Greensburg, Pennsylvania, attending his first Republican convention since 2016.

Asked about the lasting legacy of Trump, Boggs said that, love him or hate him, he’ll go down in history as a “monumental individual.”

“If you’re a fan, he’ll be a (expletive) hero,” he said. “And if you’re not, he’ll be a villain. That’s where we’re at these days.”

Former President Donald Trump and vice presidential candidate JD Vance take part in the festivities on the second night of the Republican National Convention in Milwaukee on Tuesday, July 16, 2024. (Photo by Hudson French/News21)

News21 reporters Hudson French, Donovan Johnson and Josie Malave contributed to this story.