This year’s election marks the first amid the rapid rise of artificial intelligence, and that has regulatory agencies, elected officials and voters on alert. News21’s Nate Engle generated this photo using Stable Diffusion 3, an AI image generation model.

Our content is free to use with appropriate credit. See the terms.

CONCORD, N.H. — Kathleen Sullivan always turns her phone off when she goes to dinner. But when she checked her messages an hour into a Sunday night out in January, she was surprised to find a slew of unknown numbers in her call log.

One had a woman’s name attached, so Sullivan rang back.

“I got a call from Joe Biden,” the woman said.

Sullivan, a longtime fixture in the New Hampshire Democratic Party, was baffled: President Biden had called?

Around 10,000 people in New Hampshire got the same call on Jan. 21. They included a retired biology teacher in Barrington, a doctor in Dover, a board member with the League of Women Voters in New London – even Sullivan’s sister in Manchester.

But the call wasn’t from Biden or his campaign. It was generated using artificial intelligence.

Placed in the days leading up to New Hampshire’s presidential primary, the call depicted the president urging Democrats to stay away from the polls and to instead “save” their votes for the November election. It even included a signature Biden catchword – “malarkey” – and instructions to call Sullivan’s number to opt out of future calls.

Hear the call:

The New Hampshire robocalls quickly became national news, turning Americans’ concerns about the emerging technology of AI into a domestic case study for its misuse in elections.

“To me, there’s no greater sin than trying to suppress the vote in an election,” Sullivan said, issuing a warning to others: “You have to be very careful and know that there are bad actors out there who will lie and cheat in order to win an election. … There’ve always been bad actors who are willing to do that. They just have many, many, many more tools at their disposal now.”

A 2023 Pew Research Center survey found that Americans are increasingly concerned about the role of AI in their daily lives.

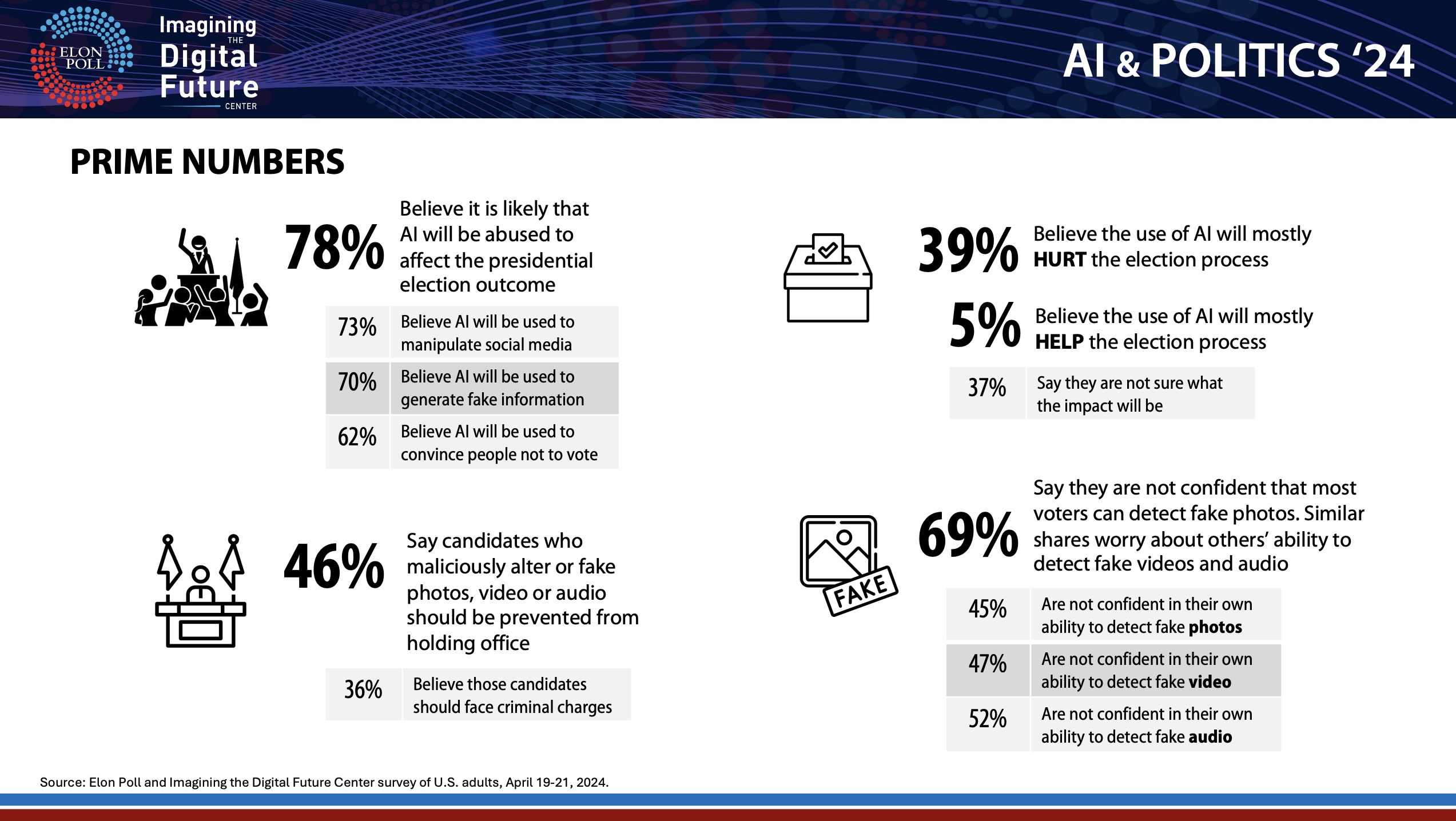

And according to a May survey by North Carolina’s Elon University, 78% of Americans think AI will be abused to affect the outcome of the presidential race, while 69% don’t feel confident that most voters can detect fake media.

This year’s election marks the first amid the rapid rise of AI, and that has regulatory agencies, elected officials and voters on alert – ahead of November and beyond.

“Trust is a really important element to a functional democracy,” said Ilana Beller, who leads efforts to regulate AI at the state level for the advocacy group Public Citizen. “The more that there is … deepfake content, and the better it becomes in terms of quality, it will become less and less possible to discern what is real and what is fake.”

In May, Director of National Intelligence Avril Haines told the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence that innovations in AI have allowed foreign actors “to produce seemingly authentic and tailored messaging more efficiently, at greater scale.”

That same month, according to media outlets, a bulletin issued to law enforcement warned that “a variety of threat actors will likely attempt to use (AI-generated) media to influence and sow discord during the 2024 U.S. election cycle.”

Congress, however, has yet to take significant action to regulate AI in politics.

Since last fall, Minnesota Democratic Sen. Amy Klobuchar has proposed three bipartisan bills to do so. The measures would ban the use of AI to produce ads falsely depicting federal candidates, require disclaimers on AI-generated political ads, and mandate guidelines to help election administrators address AI. Yet those measures have been stalled since May.

Meanwhile, officials with the Federal Election Commission and the Federal Communications Commission are squabbling over which agency should take the lead on such regulation.

And when states try to legislate more aggressively, sometimes by compelling social media platforms to restrict the spread of deepfakes, America’s tech lobby has stepped in, working against bills in states including Wyoming and California.

In the New Hampshire robocall case, a street magician told NBC News he was paid to produce the calls by Steve Kramer, a political operative who worked for then-Democratic presidential candidate Dean Phillips. Phillips denied any knowledge of the scheme and denounced Kramer.

Glad he fessed-up.

— Dean Phillips (@deanbphillips) February 25, 2024

America should already have AI guardrails in place to prevent its nefarious use.

The next generation of executive leadership must better anticipate and prepare for the future. https://t.co/ce5k0NioeD

Soon after, the League of Women Voters filed a lawsuit against Kramer and the businesses he used to disseminate the calls, seeking a court ruling to bar them from creating deceptive communications in other elections. The case is still pending.

“This will not be tolerated,” said Liz Tentarelli, president of the League of Women Voters of New Hampshire. “You cannot interfere with the election by suggesting people shouldn’t vote.”

New Hampshire League of Women Voters President Liz Tentarelli discusses her group’s lawsuit over an AI-generated robocall sent to thousands of New Hampshire voters. (Photo by Nate Engle/News21)

AI anxiety

The AI boom is happening at a consequential time for democracies around the world: Nearly half the globe will have the opportunity to vote in an election this year, and AI has the potential to strengthen democracy – or seriously weaken it.

“While AI-generated deepfakes and other synthetic media pose very real dangers for our elections, they can also be used to further creative political communication,” Shanze Hasan, of the Brennan Center for Justice, wrote in a June column.

In Pakistan, Hasan noted, an opposition leader used the technology to communicate with his supporters. Dealing with officials cracking down on his party and his own imprisonment, former Prime Minister Imran Khan’s AI-generated voice addressed the country, disputing that his opponent had won the election.

Other examples point to more nefarious motives.

As voters prepared for this year’s elections in India, an industry creating political deepfakes sprouted up. Several videos used the likenesses of dead political figures to endorse those politicians’ relatives.

In Slovakia, AI-generated audio of a candidate discussing rigging the election went viral days before that candidate lost his election last fall. And in the U.S., the Department of Justice in July announced the seizure of domains connected to a Russian bot farm that had created social media accounts depicting Americans supportive of the country’s war with Ukraine.

“There’s incredible developments on the video and audio front for a lot of generative AI applications now,” said Kaylyn Jackson Schiff, co-director of Purdue University’s Governance and Responsible AI Lab. “As it becomes really easy to make this content, more of it will be out there.”

While generative AI can trace its history to the early chatbots of the 1960s, the technology used in attempts to influence elections was developed more recently.

Launched in late 2022, OpenAI’s ChatGPT can summarize text and write articles. Generative AI companies have also developed tools that can clone people’s voices and generate images from text prompts.

Schiff said she thought AI would play a bigger role than it so far has in the U.S. presidential race. Her worry now lies further down the ballot, in smaller races where voters may know less about candidates – and in a media environment that’s decreasingly covering local news.

“It’s possible that some information that comes out could have an impact on voters,” she said.

Tentarelli has bigger fears. She remains concerned that an incident similar to the Biden robocall will happen before November.

“Whether it’s somebody doing it on behalf of one of the campaigns, or foreign influences coming in and trying to disrupt the election,” she said, “it wouldn’t take much to convince people that polls are closing early or votes aren’t counting.”

States step in

In New Hampshire, a bill to regulate AI election material was introduced in the Legislature weeks before the robocall scam went public. The measure, signed into law in August, requires a disclaimer for any deepfake of a candidate, election official or party distributed within 90 days of an election.

Left: The sun reflects off of the New Hampshire Capitol in Concord on Tuesday, June 18, 2024. New Hampshire is one of dozens of states working to pass legislation to regulate the use of artificial intelligence in elections. Right: State Rep. Dan McGuire, R-N.H., gives a tour of the New Hampshire Capitol in Concord on Tuesday, June 18, 2024. McGuire co-sponsored a bill to regulate the use of artificial intelligence in election-related media. (Photos by Nate Engle/News21)

“Nobody wants cheating in elections,” said Republican Rep. Dan McGuire, a co-sponsor of the legislation, which is backed by Democrats and Republicans.

Similar bills in other states have garnered bipartisan support.

In Wisconsin, 18 Republican and 11 Democratic lawmakers signed on to a new law requiring AI disclosures, and in Alabama, a law providing for criminal and civil penalties for material not carrying a disclaimer passed without a dissenting vote.

In the past several years, states have considered more than 90 bills to protect elections from AI, according to a database compiled by Public Citizen. Some bills have created criminal penalties, while others mandate only civil ones. Some recommend restricting deepfakes during election season.

But more than half of those bills failed to become law.

(Map by Kyle Chouinard/News21)

One challenge is designing regulations that still respect First Amendment protections on speech, said Kansas Republican Rep. Pat Proctor, whose bill to mandate disclosures on AI-generated election ads failed to make it out of the Legislature this year.

“We were trying to precisely tailor the legislation to get at the issue, which is deceiving voters by campaigns or PACs, with minimal impact on free speech of regular citizens,” he said.

Proctor said senators wanted more hearings and deliberation.

“Next year, there’s going to be all kinds of interest in this, because I think it’s going to happen repeatedly this election cycle,” he said. “I really wish we had gotten in front of it.”

‘Fighting an uphill battle’

In states such as Wyoming, California, Alaska and Hawaii, the tech lobby has been quick to weigh in on proposed AI legislation.

TechNet, a lobbying organization representing dozens of companies including Apple, Google and Meta, says it supports safeguards against the negative impacts of AI.

However, Ruthie Barko, the organization’s executive director for eight states, said: “We want to make sure that it’s not overly burdensome in a way that is going to make it difficult for this technology to be developed.”

TechNet pushes for exemptions to protect host platforms such as Facebook and Instagram from any proposed penalties, arguing content creators should be the parties held responsible for harmful material.

“Otherwise, you’re making platforms … take on some sort of internal policing of this to try to analyze every piece of content to understand whether or not it’s AI-generated,” Barko said.

In Wyoming, Sen. Chris Rothfuss, a Democrat, wanted people misled by deepfakes that weren’t properly labeled to be able to seek damages from individuals who post the content. His committee’s bill allowed people to also sue to stop the spread of deepfakes.

An early version of the bill did not include an exception for internet service providers like Verizon. Even after an exemption was added, however, the measure died. Rothfuss believes the tech lobby played a substantial role.

“We saw the level of opposition pretty clearly and knew that we were going to be fighting an uphill battle,” he said.

Rothfuss has reviewed AI legislation in other states, and he said most bills miss the mark because they’re going after the wrong people – regulating campaign officials and candidates who, for the most part, are following the rules and being transparent.

“The problem will come from somebody not holding their hand up and saying, ‘I’m producing a fake video,’” but from someone doing so “illicitly in a basement somewhere,” Rothfuss said. “That’s what you want to try to target … and none of those bills do anything about that.”

California Assemblyman Marc Berman, whose district includes tech hub Palo Alto, sponsored the state’s 2019 law banning distribution of “deceptive audio or visual media” of a candidate within 60 days of an election. The law allows candidates to seek a court order to prohibit the spread of the media and pursue damages against whoever produces it.

This year, Berman introduced a new measure, approved by the Legislature in August, to require large online platforms – those with at least 1 million California users – to block or label deceptive or inauthentic political content, depending on its proximity to an election.

Under the measure, it would be up to the platforms to create a system for California residents to report violations.

TechNet joined with other tech advocates to oppose the bill, saying it’s based on the “false assumption that online platforms definitively know whether any particular piece of content has been manipulated.”

The advocates note that many tech companies already voluntarily participate in an initiative to develop and implement best practices in this area. Some of tech’s top players – including Google, Meta, OpenAI and TikTok – also signed on this year to the “AI Elections accord,” committing to work to detect deceptive election content and address it on their platforms.

In May, OpenAI published a report about how it disrupted “deceptive uses of AI” connected to operations in Russia, China, Iran and Israel.

Berman says if platforms know, or should know, that a piece of content violates AI laws, they should act. He added that voluntary efforts provide a roadmap but lack enforcement and aren’t a replacement for government regulation.

“Companies have massive pressures on them to get more customers, to get more revenue,” he said. “So, if there’s a decision between significantly increasing revenue or adopting best practices when it comes to risks and safety, I think that they’re going to try to significantly increase revenue.”

‘Just the beginning’

With no federal law related to the misuse of AI in elections, the New Hampshire robocall lawsuit relies on the Voting Rights Act of 1965, arguing the calls amounted to voter intimidation.

John Bonifaz, co-founder and president of Free Speech for People, represents the League of Women Voters in its lawsuit over the AI-generated Biden robocall. Bonifaz believes this is the first federal case challenging the use of AI to interfere in an election. (Photo by Nate Engle/News21)

John Bonifaz is co-founder of the legal advocacy group Free Speech for People, which represents the League of Women Voters. He believes the group’s lawsuit is the first federal case challenging the use of AI to interfere in an election.

“Our focus is defending our democracy, which includes protecting the right to vote and our elections,” Bonifaz said. “When you have this kind of use of AI … you’re directly attacking the right to vote. You’re attacking the integrity of our elections.”

Three voters who received the calls are also part of the lawsuit: retired teacher Patricia Gingrich, Dr. James Fieseher and Nancy Marashio, a member of the League of Women Voters’ state board. They’re requesting damages, along with injunctions against Kramer and the companies he worked with.

In a twist to an already strange story, Kramer has since admitted to devising the robocall, telling NBC News that he did so to warn about the dangers of AI in politics.

Kramer, according to NBC, compared himself to American Revolutionary War heroes Paul Revere and Thomas Paine, and said his intent was to prompt more oversight of deepfakes.

“For $500, I got about $5 million worth of action, whether that be media attention or regulatory action,” he said in the interview. He said he had also commissioned an earlier robocall, impersonating South Carolina Sen. Lindsey Graham, that went to hundreds of primary voters.

In addition to the federal lawsuit, Kramer faces 26 criminal counts in New Hampshire for voter suppression and impersonation of a candidate. The FCC has proposed a $6 million fine against him. The agency announced on Aug. 21 that Lingo Telecom, a Michigan-based voice service provider that distributed some of the calls, agreed to pay $1 million to resolve an enforcement action against the firm.

Voice Broadcasting Corp. and Life Corp., affiliated companies based in Arlington, Texas, that provide robocalling services, are also defendants in the federal lawsuit.

Lawyers for the companies did not respond to multiple requests for comment. Kramer referred News21 to his spokesman, who declined to comment.

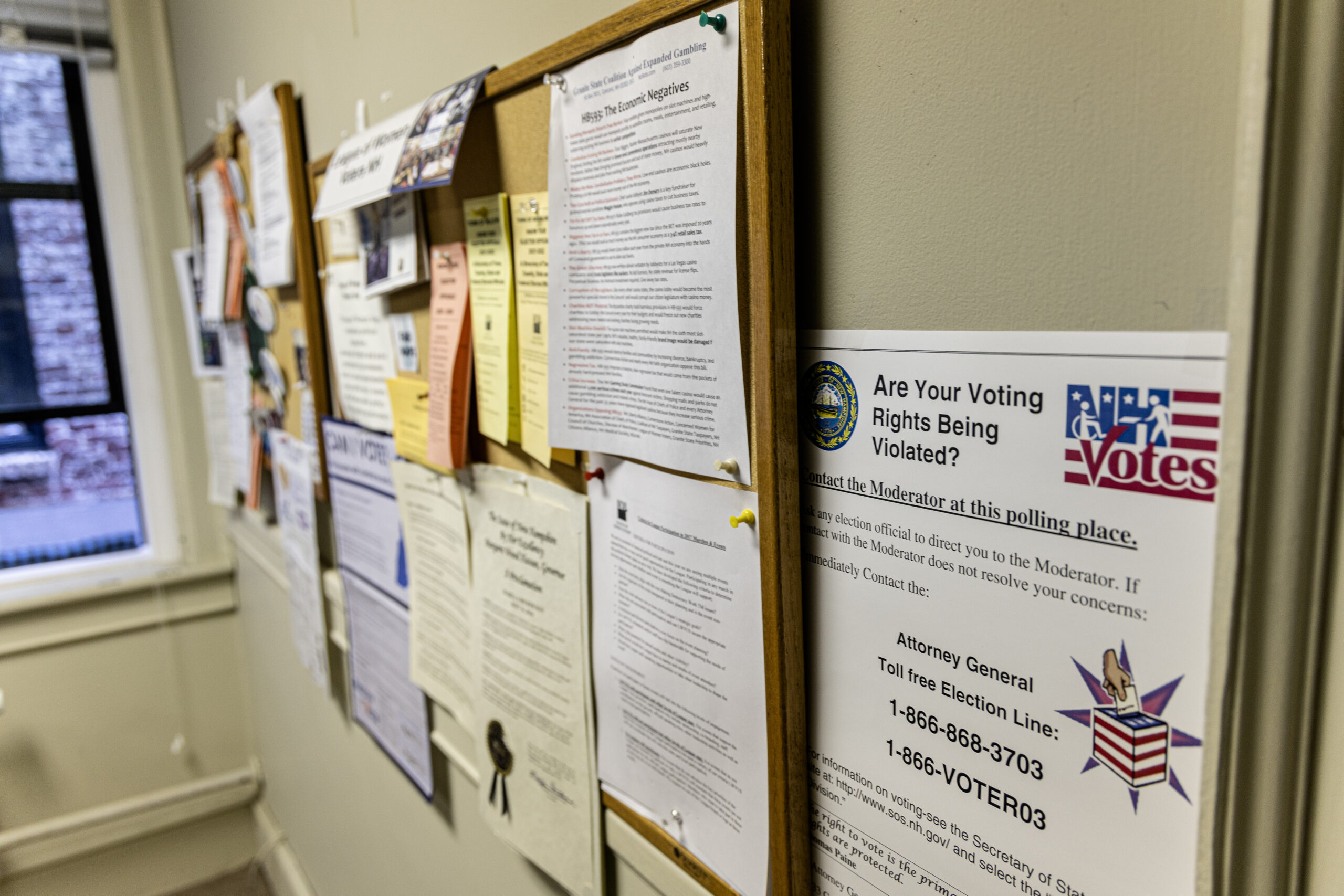

Left: Information about voting rights hangs from the wall of the New Hampshire League of Women Voters’ office in Concord, N.H. Right: The New Hampshire League of Women Voters warns voters about “bad actors” who may try to influence elections with materials such as this pamphlet. (Photos by Nate Engle/News21)

In court records, the companies said they had no knowledge of the contents of the robocall before it went to voters. Lingo noted that preventing the distribution of illegal robocalls – without illegally listening in – is a complicated, industrywide problem that won’t be solved by an injunction against a single company.

Exactly how the government plans to address the use of AI in politics remains an open question, in part because officials themselves can’t agree on a path forward.

In February, after the attorneys general of 26 states called for restrictions on the use of AI in marketing phone calls, the FCC ruled that calls made with AI-generated voices are “artificial” and, therefore, illegal under federal law.

In May, FCC Chairwoman Jessica Rosenworcel went further. She wants the agency to consider requiring a disclosure for AI content in political ads on television and radio. However, Commissioner Brendan Carr said the FCC has no authority to do so and called the idea “misguided” and “unlawful.”

The FEC also seems split over the idea. Its chairman sent a letter to Rosenworcel saying her proposal falls under the FEC’s jurisdiction.

In late July, the FCC advanced the proposal and said it would help “bring uniformity and stability to this patchwork of state laws.” It’s unclear if the FCC will finalize the new rules before the November election.

In a series of letters to the CEOs of major telecom companies, Rosenworcel pressed for details about how they’re working to prevent another situation like the one in New Hampshire.

“This is just the beginning,” she wrote. “As AI tools become more accessible to bad actors and scammers, we need to do everything we can to keep this junk off our networks.”

News21 reporter Nate Engle contributed to this story.