Our content is free to use with appropriate credit. See the terms.

SALT LAKE CITY – John Fitisemanu distinctly remembers the first time he read the U.S. Supreme Court rulings that deemed him unworthy of United States citizenship merely because of where he was born – the territory of American Samoa.

“How (can someone) leave a statement stating that you’re a ‘savage’ and you’re uneducated and you’re not qualified to be a U.S. citizen?” he says, standing outside the courthouse where he launched a battle to overturn those rulings and compel the government to extend birthright citizenship to all American Samoans.

It’s a battle he lost. Now, the 59-year-old grandfather, who has lived in the U.S. since he was 14, still cannot vote. His nephew, Jake Fitisemanu, is running to be the first Samoan in the Utah House of Representatives, yet John can’t seek office, serve on a jury or sponsor family members for immigration.

“You’ve got to work, pay your taxes and be quiet,” he says.

Nearly 4 million people live in the five inhabited U.S. territories of American Samoa, Guam, the Northern Mariana Islands, Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands. But their ability to participate in American democracy has always been limited, a constraint legal scholars, civil rights advocates and U.N. officials describe as unethical and unconstitutional.

Residents of territories hold presidential primaries and caucuses and appear in roll calls at the Democratic and Republican national conventions, but they cannot vote in general elections. Each territory elects one representative to the U.S. House, and while those representatives can serve on committees, they cannot vote on legislation – even bills they propose.

“The U.S. has millions of people living in the territories who are totally subject to federal power but have no meaningful way to shape the federal policy and policymaking apparatus that influences their day-to-day lives,” says Alejandro Ortiz, an attorney with the American Civil Liberties Union’s racial justice program.

For years now, the ACLU and others have urged the Supreme Court to reconsider these rulings, known as the Insular Cases, which determined the Constitution only partly applies to territories. The Department of Justice recently criticized the “racist rhetoric and reasoning” of the cases, yet they remain on the books.

While debate over the rulings persists, the territories continue to weigh how to move forward, whether by winning the right to fully participate in American democracy or by pursuing independence. Puerto Rico has long considered statehood. Separate movements for statehood and independence exist in Guam. And the Virgin Islands is fighting for more autonomy.

Left: John Fitisemanu stands in front of the Utah State Capitol in Salt Lake City on June 17, 2024. Fitisemanu, a native of the U.S. territory of American Samoa, unsuccessfully sued to gain birthright citizenship. Right: Fitisemanu holds his passport, which has a unique stamp identifying him as a U.S. national. While those born in other territories are automatically U.S. citizens, American Samoans are not. (Photos by Christopher Lomahquahu/News21)

Yet American Samoans are in an even more restricted position. While those born in other territories are automatically U.S. citizens, American Samoans are not – instead holding what the ACLU calls “an obscure and discriminatory status” of noncitizen nationals.

That status means even American Samoans living in the United States, such as Fitisemanu, do so without the rights granted to other Americans at birth.

“There shouldn’t be such a thing as a second-class citizen,” he says. “We fly the flag on our own island, but yet we’re not fully fledged citizens of the U.S.”

Aumua Amata – American Samoa’s delegate to the U.S. House – and government officials on the islands oppose birthright citizenship because of potential effects on Samoan culture. But in an apparent compromise, Amata recently introduced a bill to streamline the naturalization process for people like Fitisemanu.

“Instead of applying blanket citizenship to the locals and undercutting their indigenous rights, my bill attempts to … make it possible for individual Samoans to accept full citizenship before relocating to a state and without being subjected to the same bureaucratic hoops as foreigners,” Amata said in a news release.

The bill has languished in committee since October. And even if it were to reach the House floor, Amata would not be allowed to vote on it.

American-ish Samoa

The Samoan archipelago — which sits about 2,000 miles northeast of New Zealand — existed for thousands of years without its inhabitants interacting with Europeans. Samoans shared the same culture, language and decentralized, chief-based form of governance.

Then in 1899, after Germany, the United States and Britain narrowly avoided an all-out war for control of the islands, the three imperial powers struck a deal: Germany would cede the Solomon Islands to Britain in exchange for control over the western Samoan islands, and the U.S. would get the islands of eastern Samoa.

Fitisemanu’s father hailed from the western islands, now the Independent State of Samoa, but before Fitisemanu was born, the family moved to the eastern islands, today known as American Samoa. His father was enticed by the opportunity to be paid in American currency and better provide for his family. Fitisemanu grew up flying the American flag, reciting the Pledge of Allegiance at school, and seeing friends and family join the U.S. military.

It wasn’t until he attended high school in Hawaii that he realized he wasn’t as American as he’d thought. He noticed some job applications required U.S. citizenship, a status he was shocked to learn American Samoans did not have. As a result, he was denied a job in the Hawaii state prison system, a position with state benefits that some of his cousins had held.

“Other jobs came up, same thing: ‘You can (apply) for this one, but you can’t for this one,’” he says.

Fitisemanu moved to the mainland to attend college, then settled down in California and raised two children. After his divorce, he moved to the suburbs of Salt Lake City and stayed after meeting his second wife, Jennifer.

But the question of why he wasn’t a citizen always lingered.

One night, while searching for answers online, he came across a Facebook post by Neil Weare, an attorney born in Guam. Weare is the co-founder of Right to Democracy, a nonprofit devoted to dismantling the Insular Cases and allowing territorial residents to participate in the democratic process.

“Why aren’t people marching in the streets?” he asks. “To be denied basic things like voting rights or citizenship or self-determination, these are core, not just U.S. democratic and constitutional principles, but human rights.”

After lengthy discussions with Weare, Fitisemanu decided to fight for his rights in the most American way possible: a lawsuit.

Along with two other American Samoans living in Utah, he sued the U.S. government, arguing the 14th Amendment grants individuals born in American Samoa birthright citizenship. The plaintiffs also called on the Supreme Court to overturn the Insular Cases.

When the District Court of Utah ruled in favor of the plaintiffs in 2019, Fitisemanu rushed to fill out his voter registration form, eager to participate in his first election.

Twenty-four hours later, he felt like he’d been punched in the gut. The federal government had appealed, putting the lower court’s decision on hold. An appeals court later overturned the original ruling, relying on one of the Insular Cases that warns of “the nationalization of savage tribes.” And the Supreme Court declined to hear the case.

The government of American Samoa opposed Fitisemanu’s case and urged the Supreme Court not to intervene, writing that the “petitioners’ attempt to force birthright citizenship on all American Samoans threatens numerous aspects of Faʻa Sāmoa – the islanders’ way of life.

American Samoan officials have made this argument for decades.

American Samoa was never conquered or purchased by the United States. Instead, a group of matais, or chiefs, entered into what were known as Deeds of Cession with the federal government in 1900 and 1904, on the condition that the U.S. respect their Faʻa Sāmoa.

In the 20th century, some territories, such as the Philippines, gained their independence, while other territorial residents were made citizens by official acts of Congress. American Samoan leaders rejected those options, arguing the Deeds of Cession protect their cultural autonomy, including a system that prohibits land ownership by anyone who is less than half Samoan.

One told Congress: “Washington should not force anything down the Samoans’ throat.”

Officials today still prefer this arrangement, Amata has said, “due to associated benefits in the form of traditional government and indigenous land rights.” Ninety percent of land there is held communally, no U.S. citizens may serve in the legislature, and only matais are allowed to serve as senators.

American Samoans themselves are divided over whether their classification as U.S. nationals is a special privilege that lets them keep their land and way of life, or a punishment that deprives them of fundamental rights.

Charles Ala’ilima, a lawyer based in Pago Pago and co-counsel on Fitisemanu’s case, believes applying the U.S. Constitution, and citizenship, to American Samoans would not interfere with Faʻa Sāmoa.

“The U.S. Constitution is not made to say, ‘You live this way,’” Ala’ilima says. “You live the way you want, as long as the way you live doesn’t interfere with the basic, fundamental principles of our society.”

In 2012, Ala’ilima worked on another citizenship case with five American Samoans, three living in the territory and two in the U.S. The plaintiffs included a woman who lost her state government job in Seattle due to her lack of citizenship and a Vietnam veteran who faced legal obstacles to bringing his wife from American Samoa to Hawaii when he needed medical treatment.

The government of American Samoa maintains there is no movement for citizenship, with Amata at one point calling Fitisemanu’s case the product of “special interest lawyers … focused on a national agenda.”

‘Nobody wants anything like that’

Even in Fitisemanu’s family, views on citizenship are varied. His siblings, he says, were upset about seeing his name in the news. “They said, ‘Hey, nobody wants anything like that. They just want to be left alone.’”

The topic recently came up when one of his cousins, an immigrant from Independent Samoa, called to celebrate obtaining U.S. citizenship. Then she asked why Fitisemanu doesn’t just apply, too. It’s a question Fitisemanu has heard from many relatives who have completed the lengthy, expensive process – complete with biometric interviews and a civics test.

The price of citizenship, $710 for the online application fee alone, was a major factor at one point. Fitisemanu imagines that’s the case for others coming from the islands, where some earn as little as $6 an hour. The median household income in 2019 was just under $30,000.

Fitisemanu is now better positioned to pay the fee but said it was never just about the money. As someone born on U.S. soil, he firmly believes he should not have to apply for naturalization.

“I had to sit down and explain to (my cousin), ‘Yes, I can do that, but there’s a system that you need to work with in order for us not to pay,’” he says.

Fitisemanu’s niece, born in American Samoa, recently joined the Army – a common decision in the territory, which boasts the highest rate of military enlistment of any U.S. territory or state. Fitisemanu said his niece was shocked to discover a limit on what rank she could achieve and mistakenly believed service would grant her citizenship.

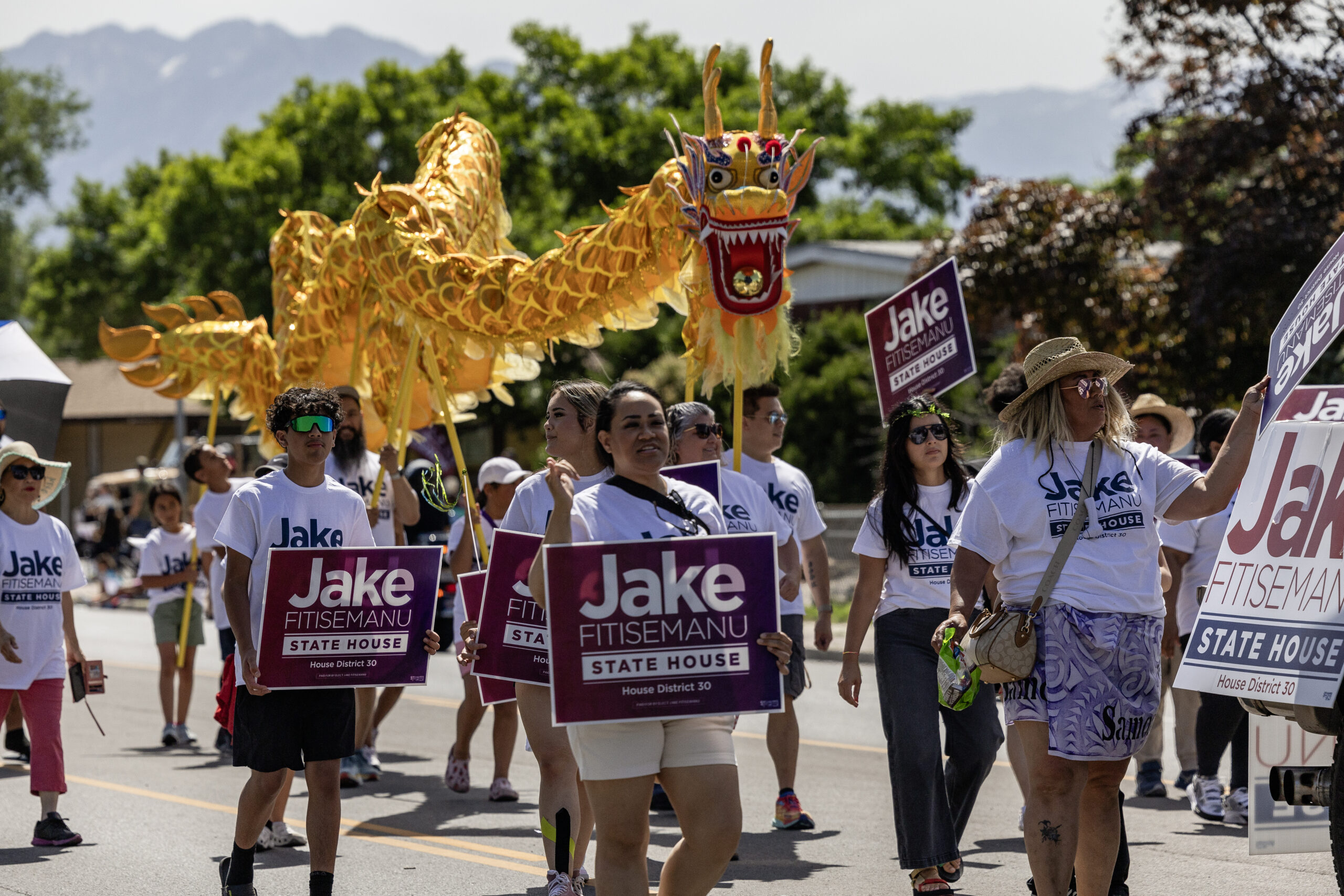

Left: Jake Fitisemanu greets attendees at the WestFest parade in the Salt Lake suburb of West Valley City. Unlike his uncle, Fitisemanu is a U.S. citizen and is running for a seat in the Utah House. Right: Supporters of Jake Fitisemanu walk in the WestFest parade. If elected, Fitisemanu would become the first Samoan in the Utah House. (Photos by Christopher Lomahquahu/News21)

Fitisemanu’s nephew, Jake, was born in New Zealand but was automatically an American citizen thanks to his Honolulu-born mother. He has family in both Independent Samoa and American Samoa. The 43-year-old is running for a seat in the Utah House, a position no Samoan has held.

Jake was in the courtroom during his uncle’s case to offer support, but he told News21 he does not take a stance on citizenship, adding that it’s up to the people of American Samoa to decide.

In his own way, Jake has spent decades fighting the effects of colonization on Samoans. As co-founder of the Utah Pacific Islanders Health Coalition, he’s worked to combat high rates of obesity and diabetes in his community.

“Our culture, our history, is one of progress and evolution and development,” he says, referencing Polynesians’ long history of navigating uncharted waters. “Stepping into spaces that may be new to us here, like politics … it’s just a continuation of that voyage.”

In the late 1800s, people from the South Pacific were exposed to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints through missionaries. Some eventually made their way to Utah and established their own communities, complete with churches featuring sermons preached in their native languages. Today, Utah has a higher proportion of Pacific Islanders than any other state in the lower 48.

West Valley City, a suburb of Salt Lake City where Jake lives, is one of the few cities in Utah to be majority-minority, with a sizable Asian, Pacific Islander and Hispanic population.

The town’s diverse communities, cuisines and cultures were on full display at WestFest, an annual celebration of the city’s founding.

In both English and Spanish, a speaker invited festivalgoers to sign up for a pie-eating contest. Ruth Fesili, Jake’s niece, manned a booth with her friends, selling Polynesian-inspired clothing. Jake’s party in the WestFest Parade wore leis to celebrate his Samoan heritage.

It has taken time for the local government to reflect that diversity. When Jake beat out a 16-year incumbent, he became the first City Council member of Polynesian descent.

Left: Martin Gaucin, left, Verona Mauga and Tomas Cruz, right, organize a voter engagement booth at WestFest. Right: Campaign signs at WestFest promote Verona Mauga’s run for the Utah House. Mauga, a first-generation American, says she would be the first Samoan woman in any state legislature in the continental U.S. if elected. (Photos by Christopher Lomahquahu/News21)

This lack of representation has tangible effects. A few years ago, public school districts in Utah banned students from wearing leis at graduation ceremonies. Verona Mauga, a first-generation American who is running for a House seat in a district adjacent to Jake’s, launched a grassroots movement, meeting with school board members and attending legislative committee meetings.

In the end, legislators passed a law that allows high schoolers to wear religious or cultural items at graduation.

“My grandmother and my mother taught me how to make leis, and so it’s sacred. It’s something you give someone out of respect and honor,” says Mauga, who would be the first Samoan woman in any state legislature in the continental U.S. if elected.

Left: Sagato Bakery & Café in Midvale, Utah, is run by Verona Mauga and her husband, Apollo. The bakery serves Polynesian pastries and coffee to the area’s sizable Pacific Islander population. Right: Verona Mauga stands behind a counter displaying Polynesian-inspired desserts at her family’s business. (Photo by Christopher Lomahquahu/News21)

While Mauga, whose parents were born in Independent Samoa, also stays out of the citizenship debate, it directly affects some of her supporters.

Tusi Poleki, a former coworker of Mauga’s, never wanted to leave American Samoa, especially after he landed a coveted job with the local government. But his children wanted to experience life on the mainland. His wife, Taliilagi, chose the Salt Lake City area due to the large Samoan Christian community.

“The Samoan motto is to put God first,” Taliilagi says. “If we could not find a church that we could attend, we would not be coming.”

Husband and wife Taliilagi and Tusi Poleki embrace during a service at the New Beginnings Samoan Assemblies of God church on Sunday, June 16, 2024. (Photo by Christopher Lomahquahu/News21)

Poleki, church secretary at New Beginnings Samoan Assemblies of God, where services are in both Samoan and English, says he prefers to remain a U.S. national, even if it prevents him from voting for Mauga.

“Here’s the problem: If I become a U.S. citizen, I don’t have rights to my land back home,” says Poleki, who plans to retire in American Samoa.

Fitisemanu has heard this concern from others, but he says land rights and citizenship are two separate issues. Experts agree. In the Yale Law Journal, Christina Ponsa-Kraus argues that citizenship would not threaten American Samoa’s land system, noting the Northern Mariana Islands have similar land rights that have survived court challenges.

The lack of voting rights has not stopped Poleki from being an active member of his community. His church has several programs to help the unhoused population, for example. And that, he says, is more important to him than politics.

“I’m not worried about this U.S. national, U.S. citizen (business) because I want to go back home, and I also want to be buried back home,” says Poleki, adding that it’s common on the islands to lay people to rest on their own land.

Faalae Soo, the youth pastor at Poleki’s church, also sees his national status as good enough.

“The same thing they have (is) the same thing we have; the only difference is, we can’t vote,” he says, noting that many U.S. citizens often don’t vote, either.

The past is not past

Fitisemanu displays both the American Samoan flag and the American flag on his desk at home in the Salt Lake suburb of Woods Cross.

“This is our life,” he says, gesturing to his home office. For 16 years, Fitisemanu has worked at a University of Utah medical lab, where he worked his way up to transportation specialist.

While he may have lost his fight for birthright citizenship, he doesn’t see the experience as a failure. And despite the disagreements, he and his family remain close. As the matai, he served a lead role at his aunt’s funeral.

“I believe in standing for (what’s) right,” he says. “And if the federal government doesn’t see it my way, I will stand my ground and continue to protest and see where it goes.”

Weare plans to continue fighting for the rights of territorial citizens and pushing for a repeal of the Insular Cases. He is optimistic that the Justice Department’s condemnation of the rulings could lead to action.

“I’d like to see progress faster, but these are pretty significant wins that create a path for the United States to really engage in a more meaningful way around these issues,” he says.

John and Jake Fitisemanu will keep fighting, too – each in his own way.

In 2016, Jake served on a presidential initiative for Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders. While the election of President Donald Trump prompted colleagues to resign, Jake faced a conundrum as the sole Pacific Islander on the commission: Stay so his community still had a seat at the table, or leave to make a statement against the administration’s policies?

Jake thought back to the independence movement in the western Samoan islands, when some of his ancestors chose to work from inside the colonial government and others engaged in civil disobedience.

Jake frequently finds himself thinking about the past. The Samoan term for “past” is “anamua,” with the root, “mua,” meaning “forward.” “Future” is “amulī,”with the root, “muli,” meaning “behind.”

Jake says that holds significance when he’s weighing a tough decision.

“It means that we walk into the future facing backward, meaning we’re still moving and progressing and going into the future, but we’re turned around to face the past … because the past shows us all the knowledge and the wisdom and examples,” he says.

He eventually resigned from the commission. “It’s not worth coming to a table when no one from the other side is meeting you at that table,” he says.

Fitisemanu thinks about the past, too. He wonders whether Samoan chiefs fully understood their early agreements with the U.S. because of language barriers. He questions how something like the Insular Cases could still exist in this day and age, and wonders how many people from his homeland have read the documents.

While Fitisemanu still believes he should already be a citizen, he is now considering applying for naturalization.

“It would be nice to see my U.S. citizenship before I die.”

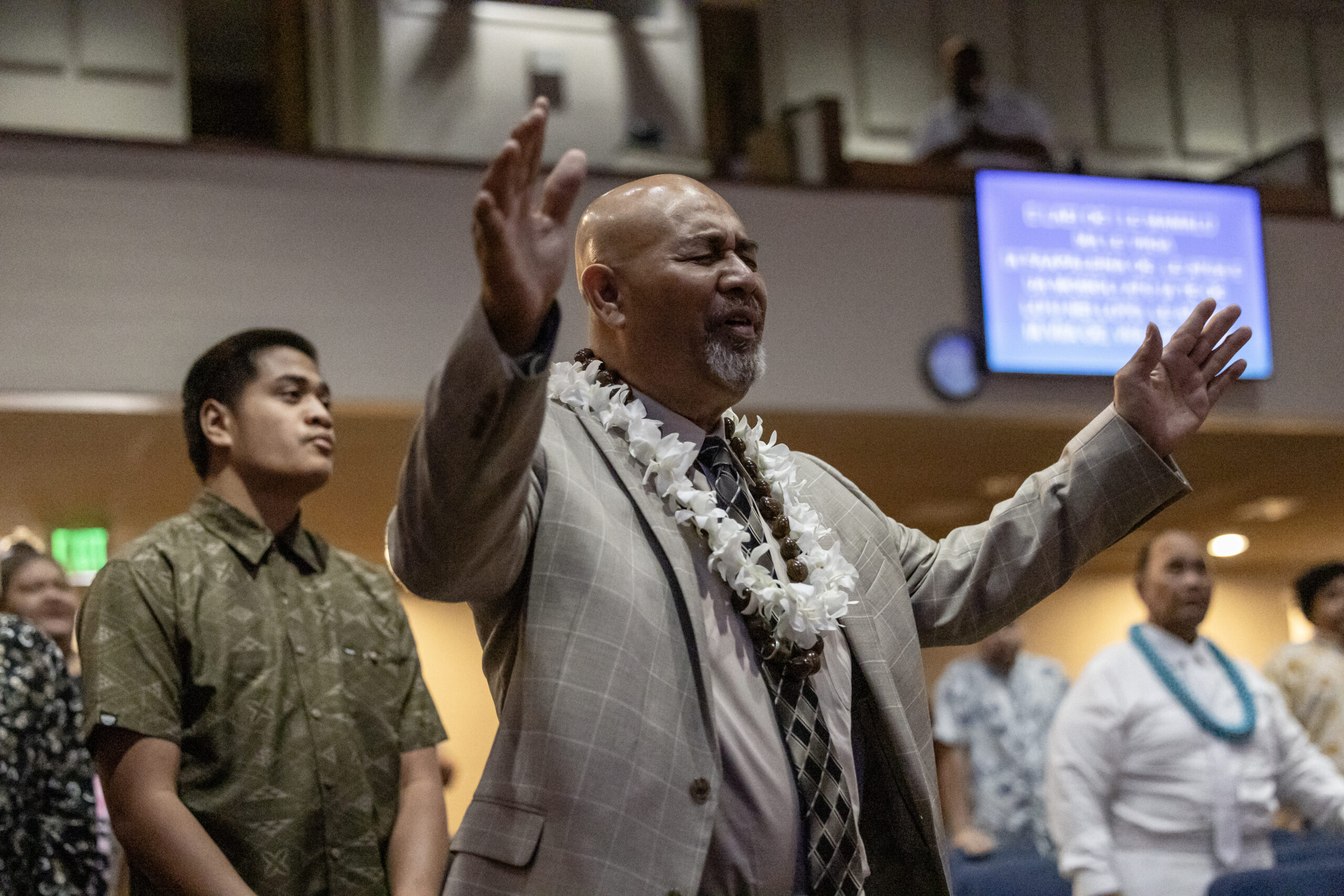

Pastor Lee Williams of the New Beginnings Samoan Assemblies of God church takes part in a service on Sunday, June 16, 2024. (Photo by Christopher Lomahquahu/News21)